In the Gatehouse Gallery on the St. Aloyseus Catholic School grounds, Sr. Helen David Brancato paints and displays her work. Almost no space is left free, and she has many more pieces to add to the rotation. On this Saturday afternoon, she was painting Biblical figures Ruth and Naomi. The piece that is nearly half-way complete is an expression of compassion between the women. Brancato says “there’s strength, but there’s gentleness at the same time.” Mercy and compassion are themes in her most recently completed works, and the focus of her upcoming exhibition at Mercy by the Sea in Madison, Connecticut.

One painting in the new exhibition is inspired by her time spent in Haiti. It is an interpretation of a last supper, depicting Haitian people gathered around an empty table. It shows the level of community that Brancato witnessed. The starkness of the empty white table cloth contrasts with the faces of the people, a diverse array of expressions that bring depth. The empty table draws attention to the strength of their community. “They nourish each other. They are resilient despite the lack of food, the lack of good government.”

Brancato studied at Moore College of Art and Design in high school, with the intention of continuing her education there to complete a Bachelors of Arts degree. Instead, she followed her intuitive call to Sisterhood and became an art teacher in Catholic Schools. While she wasn’t keen on joining any kind of order, she knew that she wanted to be of service to society. Inside, she felt that “it was destiny, there was something there” and she chose to let go of expectation and let her life unfold.

In the 1980’s, Brancato spent two years documenting Haiti’s peace and justice issues for Maryknoll Magazine. “I went with the peace delegation to Haiti, would sketch while I was sitting in the back of a truck, and then converted those sketches to paintings.”

After being exposed to liberation theology in Haiti, Brancato wanted to combine her passions for creativity and underserved populations. She saw liberation as “a theology that stems from the grassroots on up,” allowing people to become familiar with scripture and and interpret it for themselves “in order to rise up.” Brancato still holds this philosophy dear. “These people interpreted scripture with such a relational attitude to life—the life that they were experiencing. It wasn’t just words.” In 1990, Brancato would be assigned to marry her passions for art and public service by organizing The Southwest Community Center, “an art center for the people.” The art center became a communal space in south Philadelphia for people of all ages. “The philosophy was ‘We’re all teachers to each other.’ It was the university of life,” she says.

(Ida May and one of her own paintings)

“My belief is that everyone has an artist within themselves,” says Brancato. She was particularly inspired by one person, Ida May. “She’s a person who made a great impact on my life. She couldn’t read or write, but had this instinctive talent…I call her an urban shaman.” Ida May’s images were of animals, shapes, thick bold lines and colors that echoed folklore and aboriginal art—things that the Philadelphia native had never been exposed to. These pictures drew people from the farthest suburbs of Philadelphia to the art center to meet Ida May and to see more of her work. “My philosophy of working with people is to be a hands off teacher. She knew what she was doing, she knew exactly what she wanted.” Brancato’s own portraits of her adorn the walls of Gatehouse Gallery today.

“Those were the fourteen best years of my life,” says Brancato of her time spent at the Southwest Community Arts Center. It was in 2001 that she was re-assigned to teach in high school. Now an art instructor at Villanova University, Brancato can teach techniques from the depth of her experience. The institutional nature of religious life can be a strain for an artist. Painting “provided a channel where I gain all of these experiences and can put them into visual form.”

As an educator and an artist, Brancato takes an experiential approach to the canvas. She believes that, “it’s important that people use their whole bodies as they paint, as they draw, that the energy comes from the toes, through the body, out through their hands – the feet for the handicapped, or through holding paint brushes in their mouths. It’s an energy that comes from deep within, from the gut. I encourage people when I’m teaching to paint from the gut. Let go. Enjoy the process. Don’t get caught up in the product.

“I tell people not be afraid of the images that come forth. It’s therapeutic…let it come out through painting. That energy is better released then held inside of us.” When a narrative reveals itself in the paint, Brancato says that it is “actually proof that all of these images are inside of us. Based on our experience, the world of the unconscious comes out.”

<<<<<<<<<

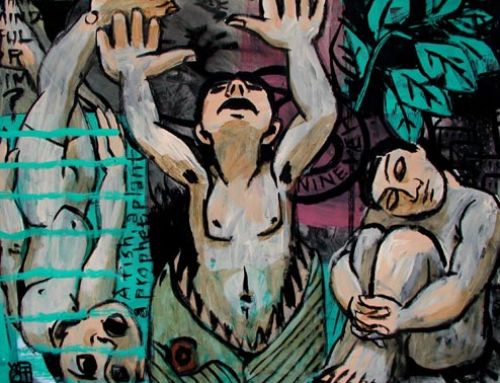

(Sr. Helen’s portrait of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera)

Exploring the rooms of Gatehouse, you might believe that you are seeing the work of a collection of artists. “I don’t have a style,” says Brancato, “it’s what I’m going through at that particular time emotionally.” Her work is boldly colored, black and white, minimal, and sometimes multimedia. While each technique and style has its own voice, her ink paintings are particularly powerful. Brancato begins by “dropping the ink on a wet surface, then trying to see something in it.” What takes shape offers a greater understanding of the emotion or heightens the voice of the subject. Finding faces and figures, Brancato then thickens lines and and lightens shapes to draw faces and forms.

While Brancato’s paintings are often images of people and concepts that are reflective of life within a community, she experiences a dialogue with each piece. At some point in time, each painting speaks to her, in a sense. It’s an exchange that she regards as spiritual, even in a floral still life. “As a painter, I’m expressing my spirit, I’m expressing all of my experiences in life, how I react to those experiences spiritually, physically…anything I paint these days has a deep, spiritual meaning.” The still life painting is quite different from the others in the studio, but that canvas was her first attempt at finding joy in painting after the death of her parents. “Those flowers have spirit. They lifted me up and got me back into painting.”

The style of a painting can sometimes affect the dialog. For the ink paintings, it can take weeks or years until she can articulate the conversation between herself and the work. With oil paintings, the process takes place during the hands-on stage of painting, or in her imagination before she begins the work. With one piece, titled “My Buddha Self,” Brancato has been holding a conversation for five years. “Maybe it isn’t time for the image to give me a message, so I just have the trust it,” she says.

My Buddha Self

See Sr. Helen’s work at:

Now-10/5/2017

Mercy by the Sea

176 Neck Rd

Madison, Connecticut 06443

Gatehouse Gallery

401 South Bryn Mawr Avenue

Bryn Mawr, PA 19010

Leave A Comment