Mary Jane Miller is not Orthodox, or a trained artist, but for the past twenty years she has practiced the tradition of Byzantine style iconography daily. Her reverence for iconography led her to study the ancient painting techniques in depth. Within the act itself, she sees a reflection of her own beliefs.

The materials used in this sacred art form are a meeting of past and present, the earth and the divine, flesh and spirit. Combined they expose a sense of awe and eternity. “The medium is egg tempera, a recipe combining egg yolk which symbolizes the raw potential for life” Miller explains, “ mixed with million-year-old dirt, which is symbolic of eternity. So, your mixing life with eternity and you create a divine image, images of Jesus, Mary, the apostles, and saints.” The practice resonates with Miller personally and spiritually. “I just thought ‘My God, I can push little particles with dirt around in an egg yolk emulsion and create beauty.’ It blended everything that I’m about. I love nature, I love life, and I love God.”

Despite her articulate and deeply passionate words about iconography, Miller says, “I don’t think I’ve ever been an artist.” She speaks with a balance of self-awareness and a sense of humor. The marriage of depth and whit is what displays her humbleness. Before she painted icons, Miller provided creative services for the purpose of paying the bills – jewelry, furniture design, painting mural. “I never thought that I would be one of those artists that was driven.” Yet, iconography gave Miller a distinct connection to her creativity and her soul when weighted against the former ways that she had used her gifts. “When I was 45 I realized that I wanted to paint these images until I die and if I stop painting them I’m never going to go back to artwork. I found what really feeds my soul.” The ancient Orthodox style is “one of the highest resonances of beauty for me. I never get tired of looking at icons.”

At times, Miller has wrestled with her choice to paint in a style that is more than fifteen hundred years old, but she sees the spiritual root of iconography as the source of its continued relevancy. “The beauty of iconography, although it may look traditional to many people, it’s not only a beautiful image and art form,” says Miller, “it’s got the spiritual components of beautiful behavior in theology. It’s got a message for humanity in the act of painting them.” The ancient style demands a certain type of structure, “but the act of painting [icons] teaches you about the depth of who you are in the sight of God.” Miller’s painting studio is a haven where she embraces the purpose that was placed in her heart. “It’s pushing around teeny tiny particles of dirt. What could get more insignificant than that? But out of these tiny little particles of dirt comes these amazing images. Images that speak of the divine, of history, of mystics, of people who prayed their whole lives.” Each grain is a part of something immense and beautiful, much bigger than if they had been left on their own. When Miller is painting an icon she becomes like a grain of sand, aware that she is part of a much larger vision in the eyes of God.

The act of painting the icons has given Miller the opportunity to meditate on biblical figures, and their stories, deeply. John the Baptist, St. Thomas, and Christ stand out as having impacted her while she painted. “In the very beginning I really identified with John the Baptist. Somebody who was just screaming in the desert who nobody wanted to listen to.” His rebelliousness captured her attention, as well as his urgency to voice what was inside of him. “Yet he is driven right into the desert silence is your greatest audience,” Miller says with a laugh. “Nobody listens to people in the desert out there screaming in front of God by themselves. I definitely felt that was one disposition of some of the early iconographers.”

Miller also felt drawn to painting images of the Madonna. “I think spiritually one the biggest things that shifted my consciousness was painting the Mother of God, The “hodegitria” the Virgin Mary and her son.” It was the relationship between Mary and Jesus in iconography that impacted Miller, “the touch of a hand, the fold of a garment, timeless love in an image.” For one year, Miller painted large images of Mary Mother of God. She wrote a book about it in The Mary Collection and created a coloring book that had space for journaling and reflection, Ancient Image, Sacred Lines, available on Amazon and Lulu. She imagines that the book appeals to inexperienced iconographers who can use the pages as a template, or patients in hospitals who are working through their illness spiritually. “You write your spiritual journey down according to who the saints are, you paint a picture of the saint, and then you talk about what a mess it is that you are in the hospital.”

Then, Miller found inspiration in St. Thomas, because he affirms human doubts. “Perhaps almost all people who are on a spiritual journey have at some point doubted ‘What attracts me to this story? Why am I doing this?’” Miller has gone to bed some evenings wondering whether she will return to the studio when she wakes, only to find herself the very next day painting another icon. During her most notable period of doubt, she had planned to teach one last class. A persistent student who had traveled from Latvia would offer her an experience that would change her perspective. Elita Sica Vavere is now Miller’s studio assistant. Seeing the art form through another person’s eyes renewed what had been three months of wrestling with the desire to stop. Miller allows divine inspiration to direct her path, not her own desire.

Iconography isn’t about the outcome for Mary Jane Miller, but about a creative process where she feels her spirit is close to God as she paints. “When I walk in the studio, it’s absolute rest. It’s rest from thinking and rest from struggling and rest from trying to figure out if the world is correct or not correct. It’s freedom from any kind of analysis. It’s like being held. Here, you can play, here you just can be in God’s presence and you don’t have to worry about anything. Just show up and do your work. It’s a refuge.”

Miller effuses humility, woven with her sharp humor, as she acknowledges that being an iconographer is a both a privilege and a gift. She says, “I feel like I’m chosen,” quickly followed by, “I am the last person God should have picked to do this.” Miller light-heartedly refrains from divulging her thoughts behind that statement, instead she rests on the sense of direction that she has toward her work. “There’s not a day where that’s not the first thing I want to do.”

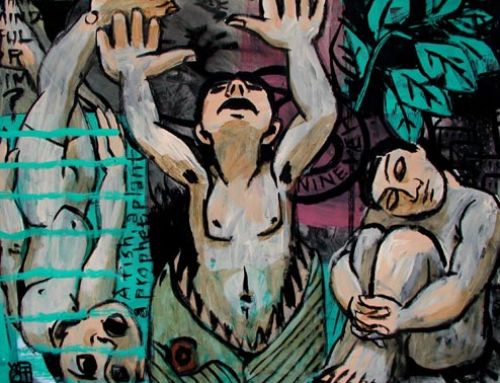

Currently, Miller, with the help of Elita Sica Vavere is working on a collection if large event style icons of women barely mentioned in the biblical texts. While she acknowledges that this may seem challenging to many, the drive came from a simple realization. When she was contemplating a portrait of the last supper, she was looking at Christ and the disciples and wondering, with all humor and seriousness, “Who cooked the meal?” Placing female figures, alongside males will bring a refreshing, and possibly rebellious, perspective to the art of iconography.

…………….

Mary Jane Miller lives and paints in San Miguel, Mexico with her husband. She also teaches iconography classes within her studio, as well as in a nearby monastery. In 2017, she will be teaching workshops in Smyrna, Florida and Lewes, Delaware. For more information, and to sign up, visit sacrediconretreat.com/#projects

Thank you very much for the article and exposure, about icons and what they can represent. It is a privilege to be added to your foundation in support of the arts and a better more beautiful world for everyone.

[…] Read more on the International Fine Art Fund blog. […]

[…] back into the eyes of the elderly who are lost in the fog dementia when she plays her guitar. Mary Jane Miller walks her students, some who have never made artwork before, through the process of intentionally […]