Refraction

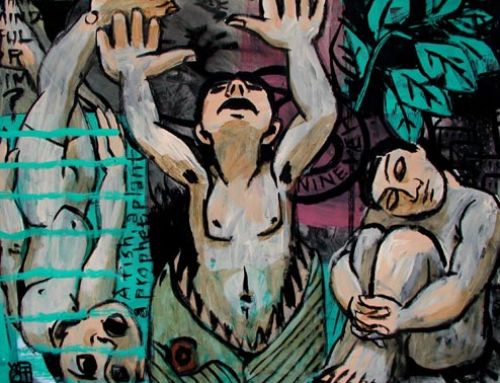

Phil Irish has continually explored spirituality and the human relationship with natural spaces since 2004. Mixed media, oil paint on panels, and digital elements in each of his exhibitions evolved into Trashing Mountains in 2014. This ongoing project conveys the immense presence of nature, as well as the weight and depth of its modification.

Our rapidly paced world is draining natural resources, driving many people to dismay. While Irish shares the feeling of horror, his artwork opens space for reflection on the potential for destruction to lead to new growth. Irish feels that mountains and oceans have an archetypal quality that resonates within us, and he asks, “How does the mountain provide a foil for thinking through where we are headed as a culture?”

Irish’s earlier works explored the relationship between humans and nature beginning with the sentimental series Maps in 2005. Irish invited people to draw him maps that led to emotionally resonant locations. He followed these paths and, if he had a significant experience in the space himself, created artwork inspired by the locale and its stories. “Interaction with, or symbolic interpretation of landscape has been a constant thread throughout my work,” says Irish. “The map paintings are about how memory imbues specific places with meaning. All of the maps come from other people—so it is also an exploration of empathy. How do I understand someone else’s story? When I visit the place of their memory, do our experiences overlap? Or are they contradictory?”

In his 2010 series Growth Charting, Irish painted disruptive, sharp strokes over serene floral images. The effect creates a tug-of-war between what is natural and what is introduced by human hands. The synthetic lines and swirls are at once separate and a part of the images.

The thread between these works, human experiences within natural spaces, comes to a violent head in Irish’s project Trashing Mountains. While Growth Charting was a step in this direction with bright, daring strokes, the works that have come out of Trashing Mountains are far larger and mostly sculptural. Irish has traded wood panel for foil and sliced canvas away from its frame to drape and mold the resolute symbol of the mountain with ease.

In the exhibitions Precipice and mount pile, elements of a traditional landscape are distorted. They communicate how the natural environment has been disturbed by destructive human interaction. Irish’s use of foil as a canvas allows the familiar to become strange, just as formerly stable characteristics of our planet are changing around us. The Polar icecaps steadily melt, and Siberia’s permafrost thins. The majestic, awe-inspiring aspects of our planet are shifting and deteriorating. In Irish’s work, Rockwell-esque renderings of mountain tops are warped, the symbol of strength distorted with a disturbing ease. Other works, like “Peak,” are collections of jagged images forming a chaotic whole. Devices that are used to deplete the earth of its resources have razor toothed jaws and loom in an ominous silence. In “Eruption,” fire somehow overcomes water, the orange, red, and black shapes pierce the placid blue as if it never stood a chance.

High Pressure

As Trashing Mountains evolves, Irish sees his vision tapering in its focus and expanding visually. “The project started in Banff, at the Banff Centre [in Alberta, Canada.] The first major exhibition was at the Gladstone Hotel, then Trashing Mountains at the Durham Art Gallery. These exhibitions used most of the same elements, but in very different contexts. In the hotel, the installation wasn’t so much distinct compositional structures as a continuous immersive experience—it started from the lobby, and rose up the grand stairs all the way to the 4th floor. The viewer would progress from the oil sand, up through the lived experiences of our culture, and arriving at the top with the grand spectacle of the mountain peak.” Precipice was held in a smaller space, which Irish felt was integral to Trashing Mountains. He calls it a “condensed statement” where painting on aluminum was a technical focal point.

mount pile, on view until August 13th at the Art Gallery of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, is a culmination of the larger and small exhibition experiences. “mount pile brings these two ways of working together. One room is installation format, while the other room is entirely metal constructions. mount pile also has a more exuberant palette—I was getting bored of blue, white, yellow, and black, which had dominated Precipice. It was exciting to lean into pinks, oranges, and even rainbows!”

Diamond

While the violence of global warming obviously strikes a chord within Irish, he also raises a hopeful question: Maybe destruction is a phase leading to new possibilities?

“It can be difficult to bring a hopeful angle into something as critical to our culture as global warming. In some ways, one doesn’t want to—because it can lead to complacency. But, actually, ‘doomsday’ messaging can also lead to complacency, because it is completely overwhelming. You hear activists speaking about this issue. That it is important to tell the stories of positive change, that change is not only possible but is taking its infant steps.”

Irish cites “The Prophetic Imagination” by Walter Brueggemann as a providing an example of positive change coming from shocking incidents. “He talks about the Hebrew prophets having to jolt awake people’s imaginations, which had been compromised by the messages of the Empire. This is very much our situation today, where we don’t believe a better world is possible—we have absorbed the complacency of our ‘first world’ entitlement, and aren’t willing to take any risks.” Spiritual rebirth has an invasive, violent aspect because it is a process of destruction to rebuild the self from within. It is painful, but the result is positive new growth. “The other part of the prophet’s task is to offer a vision of something new. And the idea that destruction can lead to new perspectives and new directions is a rich one—look, for instance, at the Gutai art movement in Japan after the devastation of the second world war.”

When asked what came first, the focus on destruction or question of possibility, Irish says both. “In the presence of the mountains, it is hard not to be stirred, to be optimistic, to think of something larger than humanity. But that, by itself, becomes a naive story. Both parts are needed to be truthful.”

Currently, Irish is sailing on an ice breaker in the arctic in the midst of an artist’s residency at the Vermont Studio Center. He’s been painting red winged black birds and letting the awe of artic ice inspire him. “You’ll be seeing arctic ice in my future paintings, as well as something with birds….”

Keep up with Irish here:

Leave A Comment